Recently, the world of cult cinema fandom was shaken by the announcement that there would soon be a third Hellboy movie… as a reboot and without acclaimed director Guillermo del Toro at the helm. This is a divisive move, largely because of how enthusiastic Mr. del Toro has been about returning to the franchise and how his interpretation was the main reason the original comic book worked its way into the popular consciousness. Replacing del Toro is a man named Neil Marshall, who was instantly derided in some circles for the simple fact of not actually being del Toro. However, if we look to what Marshall has done in his previous films as a writer and director, we might just see that a new and different direction for Hellboy will allow for some fresh perspective.

Marshall’s directorial debut was the 2002 film Dog Soldiers, the story of a military squad carrying out a training mission in the woods when they are attacked by a pack of werewolves. After discovering the remains of another training unit torn to shreds, they take the last survivor and hole up in a farmhouse as they are besieged by bipedal lycanthropes.

What’s immediately apparent about Dog Soldiers is how dated it looks, even for 2002. The film stock is grainy, the effects are all practical with stuntmen occupying large furry monster suits, and the dialogue is hokey and more than a little silly. And yet, this all feels markedly intentional, as if Marshall is purposely throwing back to the low-budget indie horror that likely inspired him in the first place. There are heavy shades of Sam Raimi (The Evil Dead) in Dog Soldiers, from the first person monster camera angles—shot in black and white because they’re dogs, get it?—to the use of light and shadow to make the most out of the limited effects budget, to the over-the-top use of gore effects to drive home the spectacle. There’s even something thematically prescient to the idea of two pack units fighting one another for survival, drawing into question just who the “dog soldiers” of the title actually are. It’s an intentionally shallow and fun experience with just enough reference and intrigue to sink one’s teeth into.

Marshall would continue this trend of horror throwback film-making with his 2005 follow-up, The Descent. Focused on a group of thrill-seeking women who decide to go spelunking to reconnect after one of their group loses her family to a fatal car crash, The Descent becomes both literal and metaphorical as, in the subterranean depths of the Appalachian Mountains, they become trapped in a network of caves and encounter something that pushes them to the depths of madness.

Though this is a return to horror for Marshall, it’s noteworthy that his visual references for The Descent are less like the indie schlock of the 1980s and are much more akin to the techniques that drove the rise in prominence horror saw in the 1970s. Relying once again on practical effects, Marshall used physical sets with intense monochromatic lighting to paint the film’s proceedings in a surreal way. Harsh reds and greens mask the artificiality of the sets and allow for the film’s humanoid monsters to scurry and lurk in the dark as the protagonists fumble and fight for their lives. There’s a lot of Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) and John Carpenter (The Thing) influence in The Descent‘s presentation, but it’s also worth noting that this was the start of a trend in gendered subversion for Marshall—placing women, who are commonly associated with victimhood in classic horror, in positions of power and competence in his films.

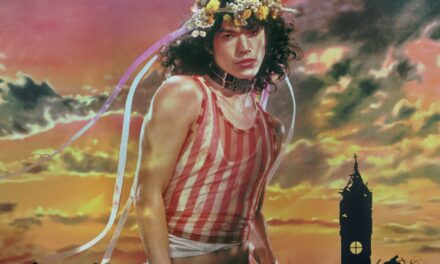

This would become even more apparent as he moved away from working strictly in horror with 2008’s Doomsday. Set in a post-apocalyptic world beset by a plague that has reduced the majority population of the United Kingdom to ravenous carriers, the upper echelons of London society start to fear that they too might fall victim to the flesh-eating plague. When news of a cure in the outlands is received, Major Eden Sinclair (Rhona Mitra) leads a dispatch to find the cure and bring it back so that the wealthy may protect themselves, discovering along the way a primal and medieval society that has developed since the diseased have been cut off from the rest of the world.

As has been the case with all of Marshall’s films thus far, homage and reference are the name of the game, but instead of going straight for horror references, he instead draws upon the works of the post-apocalyptic genre. Escape from New York, The Warriors, and, of course, the original Mad Max trilogy are paid homage heavily through Marshall’s particularly brutal and bloody lens. Major Sinclair, another of Marshall’s female protagonists, goes on a veritable sight-seeing tour through the predictions and imaginations of apocalyptic fiction auteurs of the ’70s and ’80s, even entering a society that draws more inspiration from ancient Rome than any sort of punk futurism. This is, of course, paired with plenty of over-the-top and ludicrous action beats, taking down ravenous punk-influenced hordes and participating in car chases that don’t so much involve cars as they do motorized death traps. It’s a love letter to a style of filmmaking that has fallen out of vogue, which Marshall would use as the groundwork to stage the most recent leg of his career.

The last feature film Marshall directed and wrote was 2010’s Centurion, a dramatization of the disappearance of the Roman Ninth Legion in 117 AD. In a war between the native Picts and the encroaching Roman Empire, Centurion postulates that the Ninth Legion was wiped out by a Pict ambush after they were betrayed by their scout, Etain (Olga Kurylenko), another of Marshall’s competent and badass female creations. It then falls to the centurion Quintus Dias (Michael Fassbender) to lead a handful of survivors back to a Roman camp, all while being hunted by their former scout and her accompanying Pict hordes.

Marshall doesn’t appear to draw on any direct inspiration with his sword-and-sandals film, though it is noteworthy that Centurion’s style is a marriage of the prop-driven period drama most commonly associated with Roman Empire period pieces and more modern fantasy violence, spraying blood and viscera with kill shot after kill shot in a collage of brutality. These are horror techniques brought to a more traditional action setting, giving swordplay a hardened edge in what is otherwise an operatic tale of legends. This style of action directing would serve Marshall well in the years to come, as he went on to direct episodes of television shows like Black Sails, Hannibal, and Constantine. Most notably, he brought this kind of battlefield brutality to Game of Thrones in the episodes “Blackwater” and “The Watchers on the Wall,” two of the most well-remembered episodes specifically for their intense action chops.

So what does all this mean for the Hellboy reboot, titled Hellboy: Rise of the Blood Queen? Well, Marshall has already gone on record stating that he wants this version of Hellboy to be a return to the comic book’s horror-driven roots, and he wants to use practical effects as much as possible. What’s interesting about Marshall’s style is that he is such a deliberately nostalgic filmmaker, so it will be interesting to see just how much of Rise of the Blood Queen is drawn from comic book inspirations, how much will come from del Toro’s films, and how much will be based on the action and horror films that Marshall so clearly reveres from his youth. As a director who is accomplished both as a horror craftsman and an action aficionado, Marshall is uniquely qualified to take a new Hellboy franchise in a different direction. Whether it will stand up to del Toro’s modern classics in terms of quality will remain to be seen, but there are few directors that come to mind who would be such obvious fits for the material. We’ll see when Hellboy: Rise of the Blood Queen comes out in early 2019.