Dinner In America somehow manages to both shock you and warm your cold heart, often at the same time.

Dinner In America will be a timeless classic for a particular subset of moviegoers. It continues a tradition of anarchist slacker films such as Mallrats, Empire Records, and SLC Punk with a firm grasp on what it’s like to not give a fuck in a world that demands more of us than it ever offers in returns. More importantly, and perhaps, most surprising, is that the latest feature from writer-director Adam Rehmeier is also one of the best romantic comedies in recent memory (a title it fights at every turn).

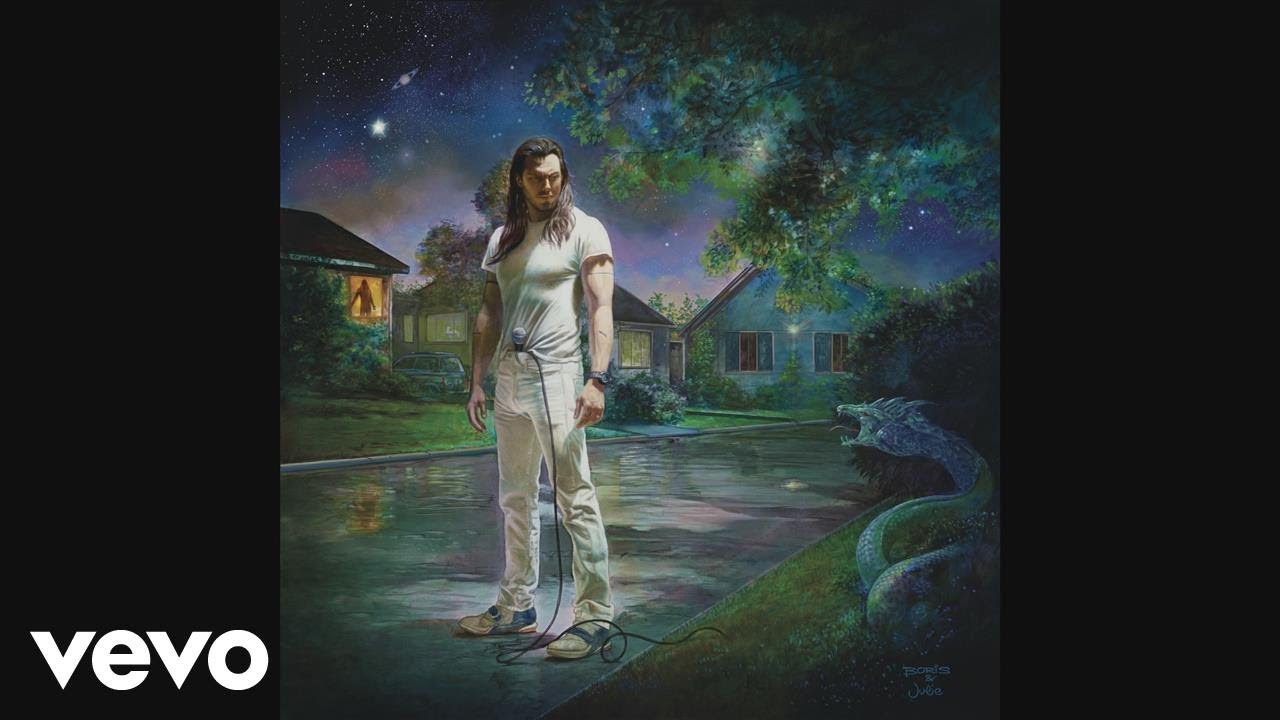

Simon (Kyle Gallner in a career-making performance) is a Detroit area punk vocalist and drug dealer currently on the lam after an awkward meal with the family of a girl he met while testing medication ends in literal flames. He’s a prototypical outcast, complete with a foul mouth, a bad attitude, and a hairstyle that draws the attention of everyone he encounters. The only things Simon seems to care about are cigarettes and music. Not because he dreams of being a star, but because it’s the only thing that makes him feel something other than utter disdain for the sheep of America.

Patty (Emily Skeggs) is a different type of outcast. A quiet and reserved young woman raised in a home that preaches religion without practicing it, Patty draws the ire of jocks, her parents, and even her employer for being perceived as slow. They call her derogatory terms for mentally disabled people, which she is not, and protest any attempt to define herself beyond their narrow-minded views. Her only escape is music and the crush she’s developed on John Q, the masked singer of her favorite band.

When Simon’s outlaw lifestyle crashes into Patty’s suburban nightmare, sparks begin to fly. Their lives could not be more different on the surface, but the emotions that drive their actions and perspectives are wildly similar. Both know the isolating feeling of a life lived outside the norm, and both want acceptance for the person that they are rather than the stereotype people expect them to become. Simon and Patty recognize these feelings in one another. However, neither is comfortable expressing it, so instead, they roam the streets of Detroit together with aspirations of living life on their terms.

Perhaps the most defining trait of Dinner is its aggressive script. Rehmeier’s characters speak their minds at all times in the most profane ways possible. Every interaction offers a bevy of four-letter words and razor-sharp insults that help keep the film fiercely in the pocket of outsider cinema. Simon would rather cut someone down than give them the chance to do the same to him, and he isn’t shy when it comes to judging the actions or behaviors of others. The film’s lone misstep in this delivery is in his one-time use of homophobic slurs, which seem to counter everything we know about him and his worldview (he doesn’t care about anything, so why care if someone is gay?).

Except for a rocky first act that suffers from the need to establish the film’s world and characters, Dinner In America is a brutally funny tale that moves at a lightning pace. The film occupies a rare space in the world of cinema where underdogs can remain mostly the same from beginning to end without facing a “big bad” or some major life event. It explores the pessimism that fuels so many people under the age of thirty without exploiting it for the sake of laughs or some false sense of cool. Instead, the humor comes from witnessing a world of seemingly average people realizing that their meaningless lives are sad in comparison to those that thrive in the margins. Simon and Patty occupy a universe they created inside a world that does not comprehend their lifestyles or love, and the kinetic energy of Rehmeier’s direction makes following their journey an endlessly engrossing affair.

The music of the film is also a highlight. John Swihart’s production work provides a lo-fi, yet bombastic pulse to the story that emphasizes the friction between the leads and society. It never rises to the point of guiding the action on screen, but it does help establish a mindset of revolt. The songs crafted by Simon’s musical alter ego do this as well, albeit with a fiercely punk sound. The standout original, “Watermelon,” will likely be a mainstay on Spotify and Apple Music playlists for alternative music fans in the same way Kimya Dawson’s soundtrack to Juno was for alt fans in the mid-2000s.

Dinner In America feels like a defining moment for the people involved in its creation and alternative culture as a whole. Rarely has a film come along that contains all the markers of classic indie cinema while benefitting from the energy and pacing of mainstream entertainment. It’s as if Edgar Wright and Kevin Smith wrote a screenplay while wearing out Fat Wreck vinyl and chain-smoking cheap cigarettes. It’s the kind of film that people will no doubt call an instant cult classic, but it’s made so well and is so damn sweet that I hope everyone will make time for it.

If you only see one indie film this year, make it Dinner In America.