Of all the holidays celebrated worldwide, no single day is loved by the Substream staff more than Halloween. With October’s arrival, the time has finally come to begin rolling out a slew of special features we have prepared in celebration of our favorite day.

31 Days Of Halloween is a recurring column that will run throughout the month of October. The goal of this series is to supply every Substream reader with a daily horror (or Halloween-themed) movie recommendation that is guaranteed to amplify your All Hallows’ Eve festivities. We’ll be watching every film the day it’s featured, and we hope you will follow along at home. Reader, beware, you’re in for a… spooky good time!

Day 30: Event Horizon (1997)

I remember it, albeit murkily: how the shadows spread up the basement stairs and stained the kitchen with darkness; how noises out in the street seemed to rattle the window panes in our dining room; how each step we took on our enclosed back porch croaked and wheezed beneath our feet; how we smirked as we accused each other of being scared—and, of course, we were.

My twin brother Alan and I had just finished watching Paul W.S. Anderson’s 1997 sci-fi horror movie Event Horizon, so, naturally, we were wandering through the house together turning on all the lights. We were only fourteen or fifteen, old enough to be left home alone and to enjoy a gory horror movie (though apparently not old enough to do both at once).

The evening had started innocently enough. After our parents left, we had crashed onto the couch in front of the TV just as the movie had begun on HBO. As a fan of science fiction, the movie looked promising: an abandoned spaceship, a missing (or massacred) crew, an engine with the ability to bend time and space. Even if we had known Event Horizon was a horror movie proper, we would have still watched; after all, horror movies rarely scared us.

We weren’t emotionally prepared for what came next. More a psychological thriller than it was about the secrets of deep space (and that’s not to mention the blood and guts splattered throughout), Event Horizon terrified my brother and I even as it fascinated us. The film lured us to hell and back, offered us glimpses of our greatest existential fears, then left us in the darkness of our own house to fend for ourselves. It was the first movie that truly scared me, that made me afraid to walk through my own house without my brother a few feet behind me, and there hasn’t been a movie that has scared me in the same way since.

I’m not sure what it is about sci-fi horror that’s so much more terrifying to me than a more traditional scary movie. Maybe it’s their remote environments—scares seem so much scarier isolated on a vessel in the vacuum of space, after all, or stranded in a faraway, unfamiliar terrain—or maybe it’s the mysteries so fundamental to the genre. Maybe it’s that terrestrial terrors provide their victims some modicum of control, if only enough to outsmart the villain, which is a luxury rarely afforded to those stuck on a spaceship.

I think this is what made me love 1979’s Alien and 1986’s Aliens at such an early age. For reasons I’ll never understand, I was allowed—even encouraged—to watch James Cameron’s sequel when I was in third grade. Sure, I was scared, but I found myself more captivated by the science and aesthetic, the way the xenomorphs reproduced, created their hives, attacked and defended themselves. I remember drawing pictures of the creatures, almost-narrative dioramas recreating battles with Colonial Marines and drop ships and power loaders. When I finally got around to watching Ridley Scott’s original, whatever fear I felt had been replaced by fascination and curiosity.

That night I watched Event Horizon for the first time with my brother, I half-expected to see the ceiling to shudder to life behind Dr. William Weir (Sam Neill) and Captain Miller (Laurence Fishburne). Certainly, both ships in the film captured that aesthetic I had learned to love from the Alien franchise. The Lewis and Clark, on which the rescue team arrives, is a gritty spaceship, ill-lit, lived-in and unloved; I could almost see the oily fingerprints on the plastic paneling that made up the living quarters, the calloused mechanical equipment and consoles on the bridge, the styrofoam cups of lukewarm coffee in their cupholders.

Their destination is the Event Horizon—a deep space research vessel with an experimental gravity drive engine that disappeared, causing “the worst space disaster on record” before mysteriously reappearing seven years later. As a ship, it’s even more impressive that the Lewis and Clark and sets the stage for a more fearful encounter. The crew enters it through an airlock attached to the central corridor connecting the ship’s experimental engine to its personnel areas at the front. This is the viewer’s first impression of the Event Horizon, a frozen, vaulting tunnel with water bottles and wrenches tumbling listlessly through the darkness. The crew’s continued exploration is lit by broad beams cast from their flashlights and occasional flashes of lightning from whatever storm disturbed Neptune beneath them; the rest is dim and hopeless.

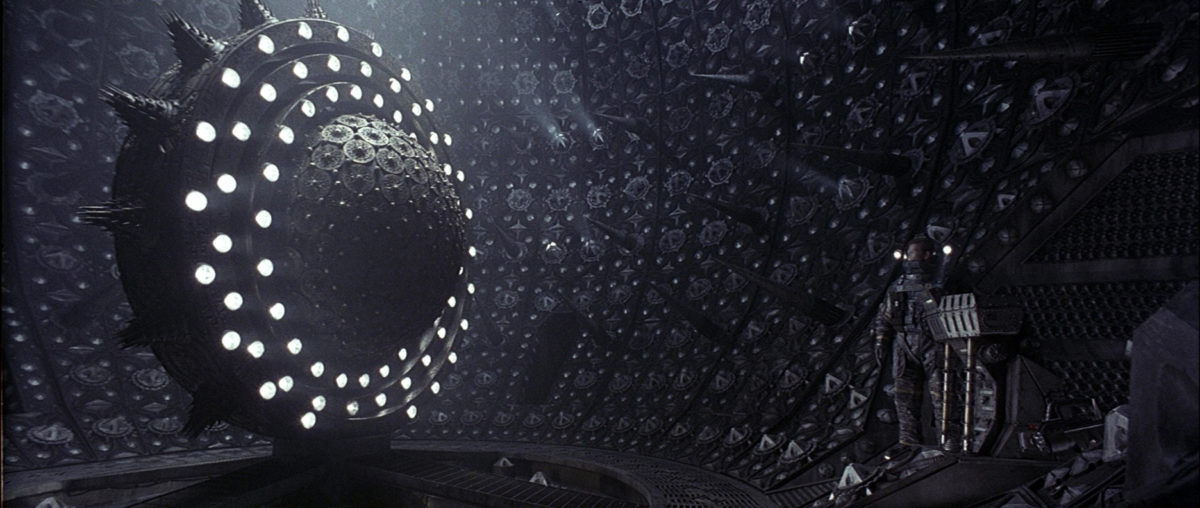

At this point in the film, my sci-fi mind was soaking up every detail about the ship, subconsciously trying to solve the mystery of the Event Horizon’s missing crew. As the rescue team explores the bridge, with its blood-smeared windows, Peters (Kathleen Quinlan) discovers a mutilated corpse floating through the frozen darkness, which explodes on the deck once gravity is restored; as Captain Miller explores the medical lab’s tomb-like silence, Justin (Jack Noseworthy) explores Dr. Weir’s gravity drive engine, a silver, spherical device around which thick, spiked rings cycle like electrons around an atom. This engine room is somehow eerier than the rest of the ship, not because of the unnatural way it wraps around the engine itself, not because of the gruesome spikes lining the walls, and not because of the stony grinding noise the mechanism makes, but because of how alive this space feels, however mechanical, compared to the rest of the lifeless ship.

Even as Justin touches the liquefied gateway created by the core engine, its rings having inexplicably aligned and illuminated, and he is tugged through it to some unknown side of the universe, I remember not feeling scared; instead, I felt that same fascination and curiosity that had greeted me on previous deep space endeavors.

It wasn’t until later that fear had quietly reclaimed my mind. It happened as members of the rescue crew (now stranded on the Event Horizon) began to experience hallucinations—of children left at home, of comrades left behind—each leading to catastrophe and chaos. Haunted by the memory of his wife, whose suicide he could not stop, Dr. Weir surrenders himself to his fears and lets the Event Horizon (or whatever entity it brought back from the boundary of existence with it) possess him; he pulls out his eyes and begins tormenting other members of the crew, even destroying the Lewis and Clark. In one memorable example, Weir traps D.J. (Jason Isaacs) in the medical lab and dissects him alive. Captain Miller finds his body spread open and hanging above the operating table, his organs in a heap beneath him.

At this point, it became clear to my brother and I that there would be no aliens lurking in the air ducts or camouflaged into the machinery; the monsters in Event Horizon are visible, hideous, and impossible to hide from. This, of course, cast me deeper into my fear.

The most terrifying part of Even Horizon, though, was where the ship had disappeared to: if not the literal Hell, then some disturbing place inspired by its popular perception. The audience discovers this during a showdown between Captain Miller (who, while attempting to destroy the central corridor of the Event Horizon, is lured into the gravity drive’s chamber by the fiery nightmare of a fallen friend) and a possessed Dr. Weir. Here, it’s revealed that the Event Horizon, when it folded space-time, traveled to another dimension entirely, “to a place you can’t possibly imagine,” a mutilated Weir tells Captain Miller. “And now, it is time to go back.”

“Hell is only a word,” he adds. “The reality is much, much worse.”

Of course, Captain Miller succeeds at destroying the ship’s corridor just as he and Weir are sucked into Hell by the gravity drive. And, of course, some members of the crew, safe and secure in the personnel area of the disabled Event Horizon, return to the saturating comfort of their stasis tubes. But at the end, the viewer is left with some big questions: Is there a literal Hell, and is it possible travel there? And what might it be like to experience Hell only to be relinquished back to a temporary reality, knowing what may await? And might technology allow us to experience what should never be experienced, and is it possible to experience it unwillingly?

I assure you, these existential questions are much more terrifying to a fourteen or fifteen year old home alone with his twin brother.

This is why my brother and I crept through the house, turning on lights, fighting about whether we should turn in the basement lights (and which of us should). We weren’t worried about seeing Weir’s slashed up face peeking through the window any more than we expected to see our nightmares incarnate stalking us as we brushed our teeth and made our way to bed. Instead, we were worried about bigger things—about the thin fabric of existence, about the bets we make about the afterlife, about how fictional science may be.

This is also why Event Horizon, little more than a bloodstained science fiction flick, is so scary. Sure, some it comes from cheap scares and explicit gore, especially considering that it contradicts the horror axiom that people are more frightened by what they don’t see. But its also because the movie impels the viewer mull over ideas much bigger than the movie itself, bigger than deep space research vessels and the storms ravaging Neptune, bigger than bending space-time. These are ideas that can’t be explored in traditional horror movies, not in the same way. In fact, these are ideas that can’t be explored in sci-fi horror movies either, only introduced.

Instead, these are ideas that can only be explored in your head when the movie’s over and the lights are turned off, and that’s the scary part.