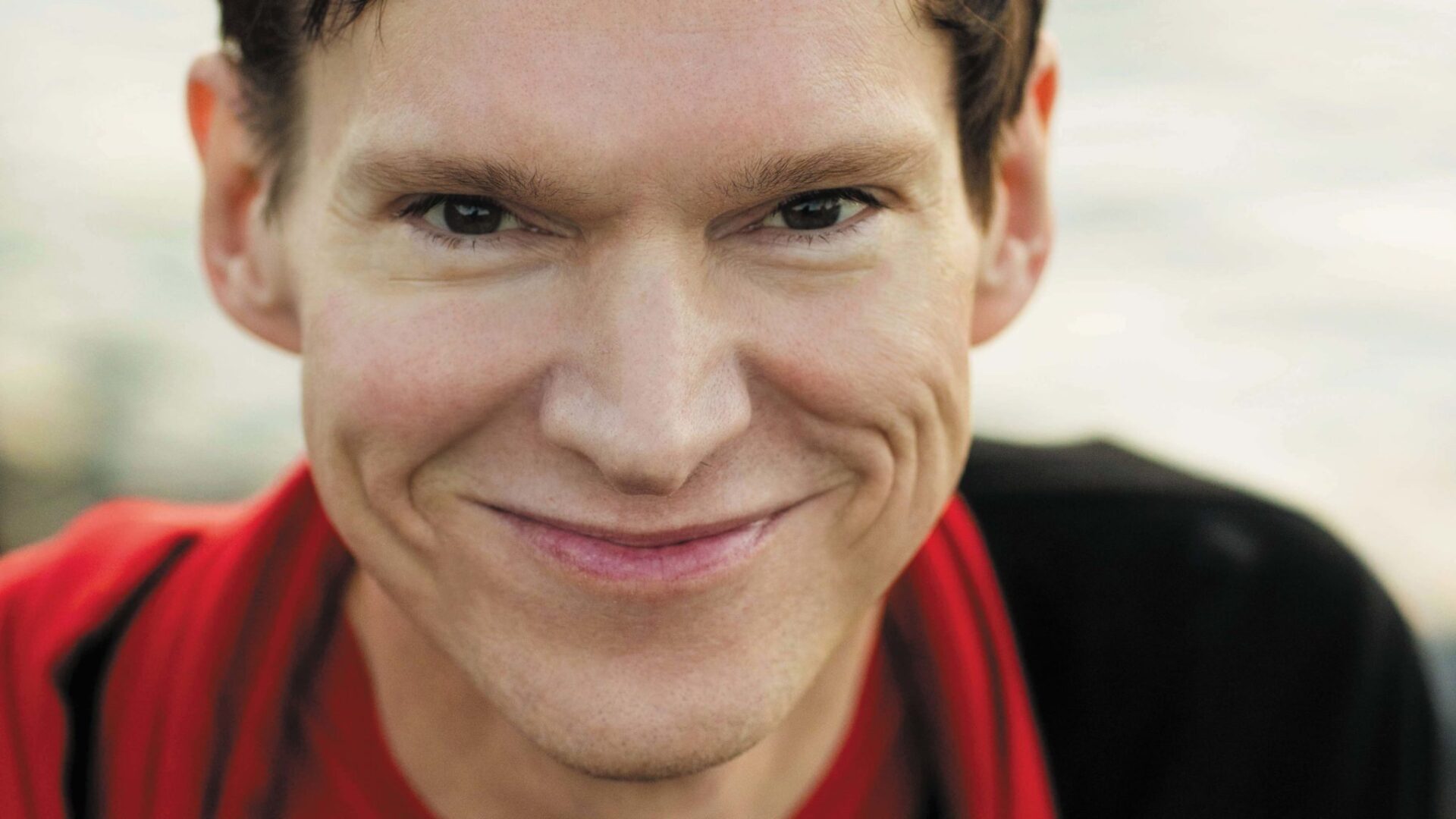

September 9th, 2009: Rob Sheffield and I are having very similar days on different parts of the East Coast. He’s afraid to leave his apartment and miss his new Beatles CD remasters, and I’m waiting to leave my 10th grade classroom to pick up The Beatles: Rock Band. Both were released simultaneously as the latest attempts to re-examine and pay respects to these four lads from Liverpool.

“The Beatles: Rock Band was actually how I learned that Ringo was the one that shouted the line, “I got blisters on me fingers!” on ‘Helter Skelter,’” Sheffield says of a time playing the game with his three-year-old niece.

“I always thought it was John so I was texting friends, asking them if I was crazy. It’s funny that I was having arguments about the Beatles with my niece. ”In his latest book, Dreaming the Beatles: The Love Story of One Band and the Whole World, Sheffield took inspiration from cultural moments like this—where a group that disbanded in 1970 continually influences current pop culture—and his own lifelong Beatlemania to add to this never-ending story.

“The Beatles weren’t a thing that just flickered for eight or nine years in the ’60s. The really weird thing and the most mysterious thing about the Beatles is that they refused to fucking go away,” Sheffield says. “It’s not that they were obscure when they first existed, but our whole sense of how big they can possibly get constantly gets showed up as lowballing.”

This proved true as the release of the expanded, 50th anniversary version of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Bandentered the charts at #1 in its first week. Although this also happened to the Fab Four in 2000—the #1 singles collection, 1, landed at the top of the 30th anniversary of the band’s breakup—those close to the classic weren’t prepared. Even Sheffield, who daylights as a writer for Rolling Stone, attests the staff wasn’t expecting such a stellar showing.

“I went to Abbey Road, and Giles Martin [son of Beatles producer George Martin] was playing me some of the album outtakes,” he recalls. “I said people were going to lose their minds, and he said he didn’t know if anybody but the hardcore, cultish fans would care.”

Dreaming the Beatles, which follows Sheffield’s similar meditation On Bowie, revisits the notion that the Beatles’ development, explosion, and disbandment was entirely new for popular music, and those revolutionary steps have echoed across genres and timelines.

“It’s beautiful that the Beatles had to figure all this out as they went along, and then after they did, it became a cliché,” Sheffield says. “All the paths they took—even breaking up and making solo records—weren’t traveled before, but now everyone accepts them as standard.”

These standards have become enough for artists left in the shadows of the narrative action. Sheffield inserts his own “instrumental break”: a list of 26 songs about the Fab Four. Each blurb connects a more contemporary name (Lil Wayne, the Replacements, to name a few) to the universe constructed by Paul, John, George, and Ringo. Even if the homages are far removed from the source material—a chopped-up vocal sample in the case of the former and a “mostly stolen” ode to a drunken night’s aftermath in the case of the latter—each chosen example calls to mind the emotional genius threaded through the core of their catalog.

“There’s so much in their music, and their personalities, that we instinctively respond to,” Sheffield says. “So much has happened in their wake in pop music, but they’re so central to all of it.”

Nothing, perhaps, is more central to pop music in than a pop star’s fandom, a concept again accelerated and deepened by the Beatles. Sheffield is quick to define “the scream”—a fiery, powerful noise built from the Beatles’ packed stadium gigs and the teenage girls filling the stands. This fan-artist connection doesn’t just end at loyalty and enthusiasm, as any history of the group will show. In 1961, there was a letter to the editor printed in Liverpool’s Mersey Beat, one of the earliest music magazines, trapping the future legends in a web of conspiracy theories.

“This happened years before Ringo was in the band, years before ‘Paul is dead.’ It’s funny that there was already something worth discovering,” Sheffield comments.

Sheffield spends the back half of Dreaming the Beatles unpacking fandom’s interpretive community, first by tackling the “Paul is dead” craze—in which the group’s faithful were certain the band’s other songwriting half had died. (Proof allegedly appeared when songs were played in reverse—even Sheffield’s own copy of The Beatles wears scratches from testing this theory—or a knife was held to Abbey Road’s coverto make a skull appear on the blade.

“Fans today have access to so much more information,” he says. “Back in the ’70s when I was growing up, we had to make do with album covers and look for clues. There were so few artifacts that we had to pore over them.”

In the case of this detective story’s modern translation, Sheffield looks to One Direction, a British band whose geographic location and meteoric rise drew easy comparisons to the FabFour’s elevated status, and a notable interaction with the pop act’s fans.

“I had written a piece after I saw them live and made a joke about how I’d like to see Harry [Styles] fold laundry, but then said that I didn’t think they did their own,” Sheffield says. “Fans sent me footage of Harry doing laundry to prove that they do—every bit of this is so documented now.”

As Sheffield also points out, Harry Styles in particular also lifts from the Beatles’ auditory scavenger hunt, referencing a Taylor Swift line in the lyrics for “Two Ghosts.” “He’s lobbing the ball over back to her court,” Sheffield explains. This phenomenon isn’t restricted to squeaky-clean radio favorites, but also hearkens back to the beginning of hip-hop’s diss tracks and battle rhymes inthe ’80s. Sheffield remembers that “on the cover of How Ya Like Me Now, Kool Moe Dee’s Jeep is parked behind him, and you can see LL Cool J’s red Kangol hat crushed under the front tire.” Even in 1987—as the Beatles ventured into solo project quirks and other ventures—their influence loomed large, serving as the “template for how stars interact with their fans and each other,” as Sheffield says.

It’s the solo career Beatles that polarize and politicize fans the most—a reality repeated today via One Direction’s split—but Sheffield’s intention was to divorce the boys from the band, even while telling the story of how each member contributed to the Beatles’ unforgettable legacy.

“Imagine the friends you had made when you were 16 and being chained to them for decades. Every time you write a song, you’d have to run it by them,” Sheffield explains. “George Harrison, who was someone who was admired and acclaimed around the world since the band broke up, still has to fight for his pecking order in the Beatles.”

Sheffield’s chapters sometimes zero in on each musician’s personal history, from vignettes of a young and sickly Ringo to a devoutly religious George during his Hare Krishna beginnings, to create a more human mosaic of such revered souls. Even as Sheffield admits, “It’s weird trying to imagine what it was like for them to try and be human beings inside this fantasy that they created for the world.” Nevertheless, Dreaming the Beatles brings the Beatles’ larger-than-life, bigger-than-Jesus magical mystery tourdown to Earth with Sheffield’s signature humor and wonder.

Sheffield recalls a time where he saw Paul McCartney debut “You Won’t See Me” live in concert—a cut taken from Rubber Soul, his favorite Beatles LP. In Paul’s oft-imitated accent (a feat practicedon Dreaming the Beatles’ audiobook version), he recreates the glee the rockstar shared with his audience—“Oh, I’ve never played this one before!”—and takes it as a life lesson. “It’s funny that fucking Paul McCartney at 75 is still adding songs to his setlist,” Sheffield says. “He was also still going after three hours. I asked myself, ‘I’m fucking exhausted, Paul. How are you still doing this?’” In that moment, the human Paul and the legend McCartney were one: an impressively agile musician still ecstatic about his old band’s tracks.

Even for long-time Beatles historians, Sheffield’s own version of the narrative still contains plenty of surprises. (Who knew the Bee Gees attempted to cover Sgt. Pepper in full?) But perhaps the biggest surprise is the author’s evolving understanding of the band’s saga long after he turned in the final draft.

“The book is done, the book is out, and I can’t change anything, but I’m still noticing things in these songs,” Sheffield says. “It’s even ridiculous that I’m still listening to the Beatles for fun.”

And just like that, his Beatles dream continues.