Films that take place in single locations with a limited cast of characters are, more than anything, showcases for character dialogue and performance, as the mechanisms for a narrative are stripped down to their barest core for whatever budgetary or production-side reasons a film may require. This style of filmmaking bears a lot of potential for independent productions and freshman directors, but it also makes it easy for anyone with a script and a camera to think they’re making the next Reservoir Dogs. Director Ramon Térmens’s The Evil That Men Do doesn’t nearly reach the heights of Tarantino’s debut film—few films do—but as far as low-budget flicks wherein we explore the psychology of a handful of people trapped by circumstance go, there’s a lot to appreciate here.

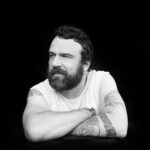

In Mexico, two cartel workers while away their days disposing of bodies and delivering the pieces to rival gangs. Benny (Andrew Tarbet) is a United States expatriate who is less inclined to violence than one might expect from one involved in the cartel, while Santiago (Daniel Faraldo) is a bit more ruthless and doesn’t care about collateral damage if it minimizes risk and gets the job done. Their commitment to their work and each other is put to the test when their boss’s son, Martin (Sergio Peris-Mencheta), brings them the ten-year-old daughter of a competing gang leader, and the men struggle with the prospect of harming an innocent girl to send a message to her father.

There’s a light charm in how Benny and Santiago discuss their work, a sort of sardonic ignorance that their work with the murdered remains of people might make them bad guys. This makes the two objectively criminal leads surprisingly likeable, and Benny quickly reveals himself as a guy in over his head through bad luck and circumstance. The script expends a little too much effort in constantly reminding us that Benny is the soft one and Santiago borders on sociopathy, but as the film wears on it becomes clear that the reason for this was to later toy with the archetypes in interesting and unexpected ways, turning would could have been a banal and predictable tale into a surprisingly committed analysis of morality and conscience.

Where The Evil That Men Do falters is in its delivery. Tarbet and Faraldo seem to be competent enough actors, but sometimes their dialogue (written by Faraldo) is a bit awkward and obvious, while Térmens’s direction leaves their delivery a bit stiff and stilted. Furthermore, the only adult woman to appear as a named character is shallow and largely devoid of agency, which feels rather uncomfortable in contrast to the relatively deep characterizations of the men. This by no means kills the engagement one feels with the material, but it does serve as a constant reminder that the production is staged and acted because that’s what it constantly feels like. It’s an interesting narrative that suffers from a lack of polish that could lend the production a more cinematic feeling.

Even so, The Evil That Men Do makes the most out of its setting and characters and in turn is a good bit of independent cinema. More than anything, it’s a modest film, making the most of the resources at its disposal and delivering a quality piece of entertainment that builds to a satisfying climax with enough twists and turns to keep it from feeling rote. Its flaws are obvious, but those sins are far from unforgivable.