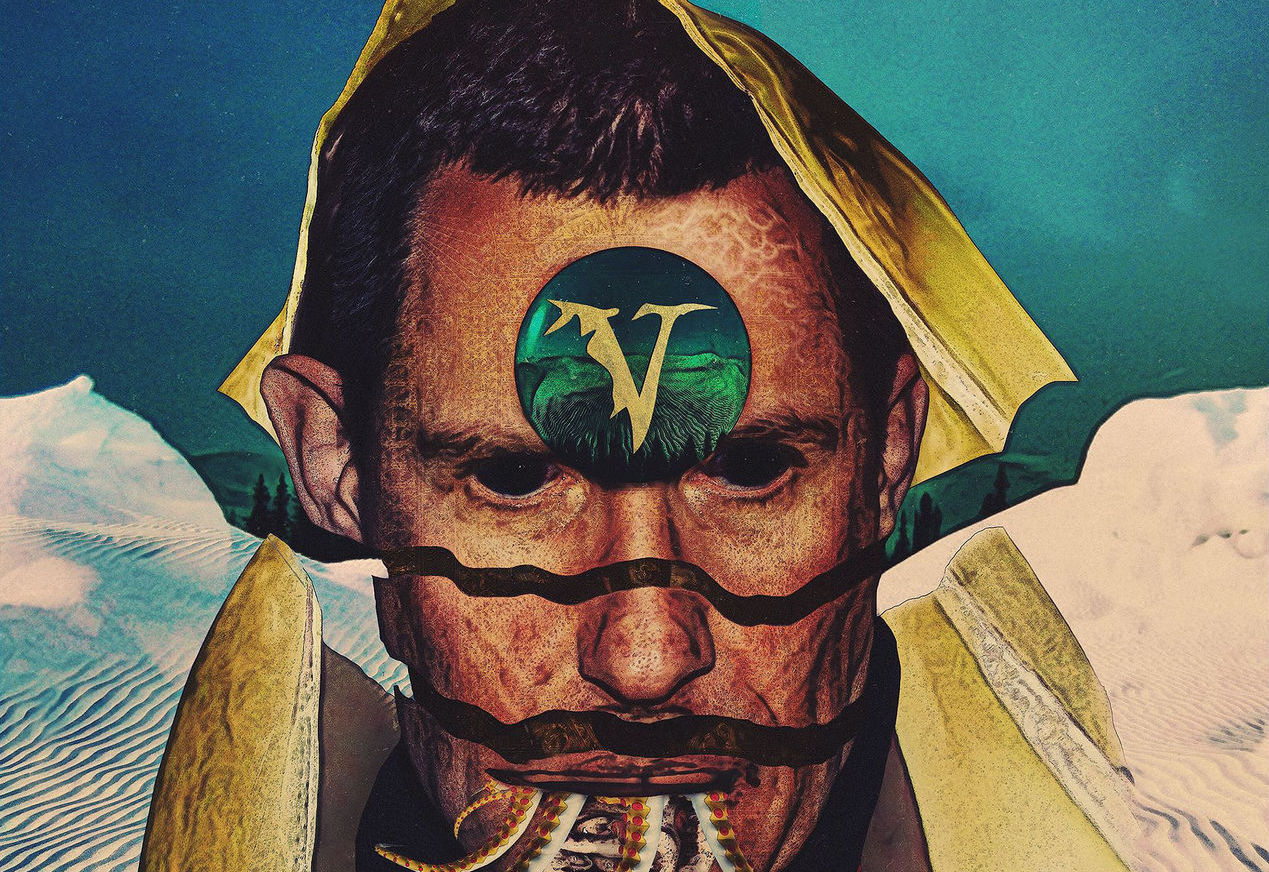

What if there were definitive proof that there is an afterlife? What would you do with that sort of knowledge? Would you commit suicide to get there all the sooner? What would be waiting for you on the other side? Would it be the Christian model of heaven, or something much more ethereal and unknowable? These are the questions posed by The Discovery, the second film from writer-director Charlie McDowell which poses some grand philosophical questions, even if the human grounding through which it asks them doesn’t quite connect as deeply as it should.

The film opens on an interview with Thomas (Robert Redford), the doctor who has discovered that neuroelectrical activity leaves the body upon death, proving that something akin to a soul departs to some other location that has not been identified. This has led to a giant uptick in suicides worldwide as people opt to end their earthly suffering for a chance at something better beyond. Flash forward a year to Thomas’s son Will (Jason Segel, unusually dour), travelling on a ferry to a mysterious island where, we soon discover, Thomas has set up a cult-like research facility to continue his research into the afterlife. On the ferry Will meets Isla (Rooney Mara), a depressed woman whom Will soon grows attached to for reasons he cannot quite grasp.

If you’re looking for a nontheological examination of regret and meaning in life’s meaninglessness, then The Discovery has a lot to offer. Even as all the principle players look forward in attempting to decipher just what the afterlife holds in store for them, they are bogged down by lives that have determinative moments where they made the wrong decisions, and this has shaped their worldviews, motivations, and, if you will, destinies. As much time is spent on remembering what went wrong as it is looking forward to what can be done right, and The Discovery quite intelligently plays more like a series of reflective questions than any sort of revelation. McDowell clearly knows better than to pretend at the answers to the questions he raises, so even as he weaves a mystery that does have a definitive climactic payoff, it doesn’t pretend to have any more insight into its high-minded concept than any of us, avoiding the prospect of becoming the proselytizer Thomas becomes to his followers.

I only wish the vessels through which this story was delivered were more empathetic and believable. The crux of the climax is built around a supposed romantic relationship between Will and Isla, but Segel and Isla are so determined to play grim, detached personalities that their romance never quite feels authentic. This is further hampered by the fact that from a characterization standpoint, Isla is little more than a depressed version of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope, a delivery mechanism for Will’s character development while her own is sidelined and secondary. For a film that wants so desperately to tap into a certain universality of the human experience, the narrative is decidedly weighed down by its adherence to tired, outdated conventions.

Still, based on the pure intellectual exercise, there’s enough to recommend The Discovery. It’s a film for philosophers, a thought experiment that puts the viewer into a mode of extreme introspection and self-discovery. It’s just a shame that the archetypes we are stuck watching perform the experiment are so much less compelling than the experiment itself.