Spike Jonze has built a directorial career for himself by being that guy. You know, the guy who’s into all the really weird shit and kind of looks at the world as if through a funhouse mirror, yet still comes off as eminently likable and relatable because we all wish we could be perhaps just a fraction as interesting as he is. Jonze only has four feature films under his belt as a director, only two of which he has written, but already he has placed an inerasable mark on the American cinematic landscape for films that are as visually stylish as they are psychologically analytical. What’s probably most interesting about Jonze’s works, though, is that each of them has something to say about the complexities of human nature, and a clear dividing line exists between the latter films that he has written and the earlier films written by the maddest of screenwriters, Charlie Kaufman.

Kaufman’s and Jonze’s first feature film, both together and overall, was 1999’s Being John Malkovich, a simple tale of a puppeteer forced to get an office job on the building’s 7 ½ floor where he meets the love of his life—who couldn’t give two shits about him—and a portal into the brain of actor John Malkovich, which they exploit for financial gain as people vie for the opportunity to live in someone else’s shoes, if only for a few seconds. Oh, and the puppeteer begins to take over Malkovich’s body gradually to make himself more attractive to the woman of his dreams, who in turn actually seems more interested in the puppeteer’s wife, but only if she is also inhabiting the body of John Malkovich. Simple, right?

John Cusack, Cameron Diaz in ‘Being John Malkovich’

Underneath all the strange and insane mechanics of Kaufman’s groundbreaking screenplay is one philosophical underpinning: solipsism. For those of you who have never taken a college philosophy course, solipsism is the idea that no one can ever truly understand someone else’s perspective because we are so trapped and shaped by our own experiences that nothing can ever bridge that gap. All three protagonists of Being John Malkovich are varying degrees of insecure and disturbed, either acting as manipulators or willingly manipulated because they don’t understand how to behave any differently. But entering the mind of John Malkovich, who is perhaps the film’s most well-adjusted character, awakens in them not only personal growth or degradation, but also encourages a variety of workaday shlubs to crave the escape, even if only for a moment. This is shown in Jonze’s direction by externally observing the principle cast from a third person perspective, yet when entering Malkovich’s mind everything is reduced to a singular point of view shot as Malkovich goes about his normal day. We all escape our mundane lives to catch a glimpse at the mundanities of the characters on screen, only their struggle for escape mirrors our own.

As cynical as that sounds, it pales in comparison to the fascinatingly narcissistic exercise of the second Kaufman/Jonze collaboration, 2002’s Adaptation. Kaufman writes himself as the title character in a movie that is all about writing the screenplay for the movie that we are in fact watching. Kaufman pulls no punches in his self-portrayal as an auteur, driven to avoid formula and conventional structure in adapting a plotless book about flowers, pushing away any sort of mechanisms that would guarantee him easy monetary success. Meanwhile, his twin brother, a fictional construct developed for the purpose of the film, writes a tacky and cliché-ridden screenplay that is met with adoration and reverence.

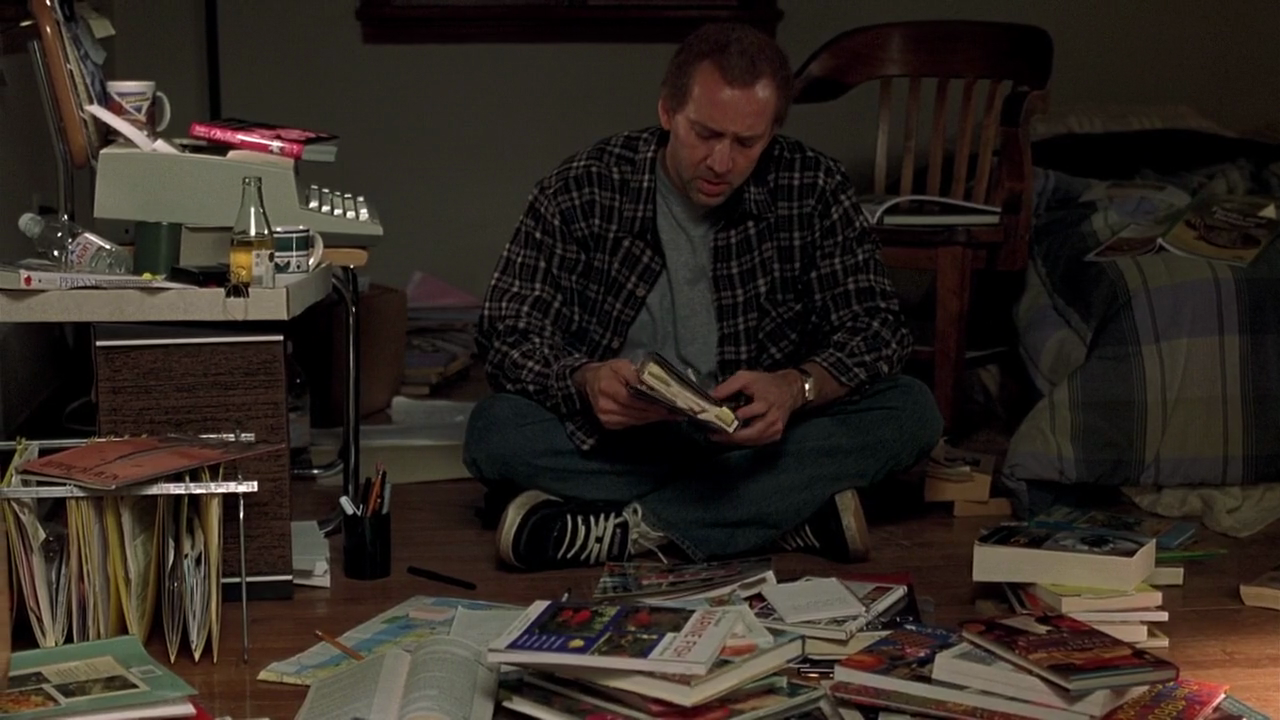

Nicolas Cage in ‘Adaptation’

The line between Kaufman and Jonze starts to become a bit more distinct in this second film, as we see that Kaufman pulls much of his artistry from self-flagellation, so what Jonze does is make Kaufman the character a much more relatable person than what the text alone would make him out to be. Kaufman is a rude, socially-awkward guy, but when compared to the sycophants and general idiocy of not only his agents and studio contacts but also the author he so admires, Kaufman is always the smartest person in the room, even as he struggles to find his way back to basics in order to make his screenplay work. To the hard edge of Kaufman’s autobiographical musings, Jonze adds his own brand of whimsy that would tonally clash if coming from another director. However, Jonze portrays the workings of Kaufman’s pretentious brain with compassion and relatability, which is something the mad writer desperately needs if his psychological inquiries are to be taken seriously by a general audience.

Kaufman and Jonze parted ways after their second film together, but Jonze dipped into writing with literary writer Dave Eggers for his third film, an adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are. Jonze’s and Egger’s screenplay greatly expands on the iconic picture book, depicting protagonist Max as being raised by a single mother and coping poorly with his older sister’s departure into adolescence and his mother’s romantic pursuits. So he runs away and impliedly imagines himself among the Wild Things, a race of beings that casually exhibit childlike emotions and mentalities, yet in their communion represent Max’s inner struggles as a literal demonstration of his inner emotional turmoil.

Max Records, Alexander (voiced by Paul Dano) in ‘Where The Wild Things Are’

Though the cynical comic edge still remains from Jonze’s work with Kaufman, Jonze’s own particular style is less about introspection and more about understanding universal truths of human psychology. Max’s eight-year-old mind is only just starting to grasp concepts like empathy and compassion, and even in his wild fantasy he is limited by certain rules of reality that his imagination cannot compensate for. The Wild Things are untamed ids that his still-developing ego is struggling to contain and control, which is something that each of us should be able to relate to as we all went through a similar process. All Jonze has done is give voice to the emotions that were too big for our young brains to handle, and Where The Wild Things Are is the artistic expression of that development.

And yet it is probably Jonze’s latest film where we see him reach the height of his individuality as a filmmaker. In 2013’s Her, we follow the exploits of Theodore Twombly, a resident of a near future where an acceptable profession is to write love letters on behalf of one romantic partner to another. The development of a new sentient operating system intrigues Theodore, so he purchases one and quickly discovers that Samantha—as she names herself—is perhaps more real than anyone he has ever wanted to pursue a relationship with before, even his ex-wife. So love starts to bloom, and the difficulties inherent in that sort of relationship push and pull them variably together and apart.

Joaquin Phoenix in ‘Her’

Now, Jonze’s view of the culture of dating and the commercialization of such is, again, characteristically cynical. Romance in the vast cultural sense is less about the connection between two people than it is the transaction of sentiment or the obligation to start a family. After all, if you aren’t “serious” about pursing a relationship, than you’re just “wasting time” as one of Theodore’s dates puts it. And yet, when it comes to the dynamics of an actual functional relationship, Jonze’s story is actually sweet and completely sincere. One would think the union of a man and a machine would be cause for exploitation or a last desperate plea of a lonely man, but as Jonze portrays it, Theodore and Samantha’s love is real and the connection they develop is dictated by more than just the circumstances of their birth. Their relationship feels real, which not only comes with the good of emotional support, but also the bad of poor communication and false expectations. With that, though, both Theodore and Samantha grow for the experience. They grow so much, in fact, that eventually they grow out of the relationship, and what they come to realize is that that’s okay. Relationships don’t need to last forever in order to mean something, and that nugget of truth is what makes Jonze’s film such a poignant examination of humanity.

It’s unclear when or if we’ll get another film from Jonze any time soon, but what is clear is that when that film does come it will have something interesting to say about the human condition. Starting from Kaufman’s harsh look at humanity’s singular loneliness in Being John Malkovich and culminating in his own tale of the hope inherent in human connection, Jonze’s outlook on humanity is looking less and less bleak as the years go by. But whether his next take is darker or continues the trend of looking for hope in our interpersonal turmoil, there’s going to be a smart commentary underneath all the visual flourish. I for one cannot wait to see what’s next.