Harper (Jessie Buckley) takes a road trip up the English countryside to a beautiful 500-year-old estate for some much-needed relaxation and solitude. The landscape is lush, full of beautiful foliage, where one can disappear from their problems entirely. From the glimpse of the first frames of Alex Garland’s Men, you see a tragedy has happened and find out that Harper is a widow. The circumstances of this get elaborated on more as the film goes on, but while Garland plays with the abstract, Men has a straightforward message with some creative forces to portray it. In all its forms, toxic masculinity will stalk you even in Earth’s most remote and tranquil places.

James (Paapa Essiedu) and Harper’s relationship was at the point of divorce before the trip happened — and the cause of his death is not specific. Was it suicide or an accident? These are emotions Harper struggles with internally throughout the film’s runtime. Up to James’s final moments, he places guilt upon her like a curse for her to live with just for simply choosing herself. In the present day, the estate’s owner, Geoffrey (Rory Kinnear), seems like he means well, but the subtle instances of dialogue hint there’s a disturbing thought pattern operating inside him. Geoffrey doesn’t allow Harper to help with luggage even though he struggles with it, makes a snide comment about flushing feminine products in the bathroom, and makes an off-hand inference to an apple Harper eats as “the forbidden fruit.”

Sometimes overt and symbolic, the allegorical religious references are left up to the audience to decide how powerful they are concerning the plot. Garland takes a scene like a woman biting an apple and later mixes it with pagan symbolism of pictures on an altar — which may have needed more time to clarify their significance to the point. Still, Men does it’s the best work when exercising the leads to the best of their abilities in a take of how suffocating male expectations can be.

Both Buckley and Kinnear are who the audience spends their time with for most of the runtime. Outside of flashbacks with Harper’s husband James and a concerned check-in from her friend, Riley (Gayle Rankin), the film is left in the more than capable hands of the duo. Buckley’s portrayal of Harper ranges from sheer anger, inner torment, and tranquil moments of peace on a whim. Harper has this immense weight placed on her unfairly at the moment when she’s fighting for her independence. Garland provides the question of the definition of love and how it can be used as an abusive weapon against someone who rightfully chooses themselves over you.

Kinnear portrays a myriad of male characters who make their offensive presence known throughout Men — from a priest who implies Harper “drove James to it” to a police officer who apprehends a naked man (also played by Kinnear) from outside the estate and shrugs the danger off. He’s even a little boy who is especially mean to Harper when she doesn’t concede to play a game. Harper doesn’t realize the constant man behind all these avatars, but that may be the point. In consequence, Men‘s invocation of horror stems from all the ways one woman has experienced microaggressions throughout her life. A bonkers third act calling upon body horror to drive that point home sends the message loud and clear.

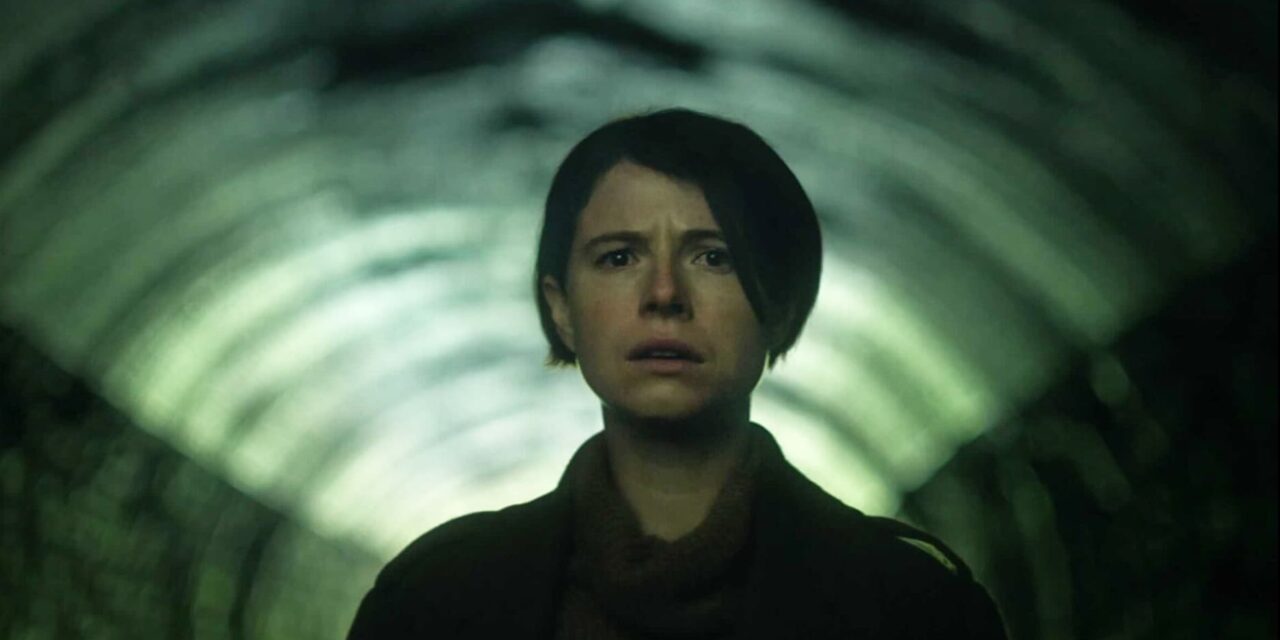

However, it’s the more serene moments interrupted by over-curious disruption that serve as the most frightening — not so much in the religious lore the film tries to use as a tie-in for what it’s saying. At one moment, Harper ventures down into the woods and finds a tunnel, where she finds brief happiness playing with the echo. It’s when a figure rises in darkness and chases her; a sadness comes over you, realizing Harper can’t even have that to herself. Much credit to the cinematography style of Rob Hardy, who uses the entire influx of nature and the colors red and green as another instance of narrative without it having to be said. The score composed by Geoff Barrow and Ben Salisbury never allows the characters on screen or the audience to slip into a comfort zone.

At the end of the all, Garland’s latest is about men (or one singular man) misbehaving. It will surely inspire some conversation because the patriarchal depiction is very present in a couple of different ways where you can interpret it. There may be more of a longing to explore the complexities of what Harper is dealing with rather than having a film have her be a societal metaphor — that being said, the acting is where everything comes together.

Photo Credit: A24