It’s rare that I feel this way about Richard Linklater, but Last Flag Flying feels like a project perfectly suited to his sensibilities. The director is known primarily for his largely plotless nostalgic hangout films, basing these trips largely on his own experiences without hampering himself with such contrivances as character arcs or narrative cohesion, but Darryl Ponicsan‘s novel is a thematically plotted series of conversations wherein the principal characters reminisce about their pasts to make points about the future. This makes a decent framework to reign in Linklater’s more meandering sensibilities, and the adaptation of Ponican’s first novel with these characters, Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail, already provides a template for how this sort of meditative journey might play out in practice. So color me surprised that Last Flag Flying is a good, if imperfect film, and for once my irritation is not with Linklater’s direction.

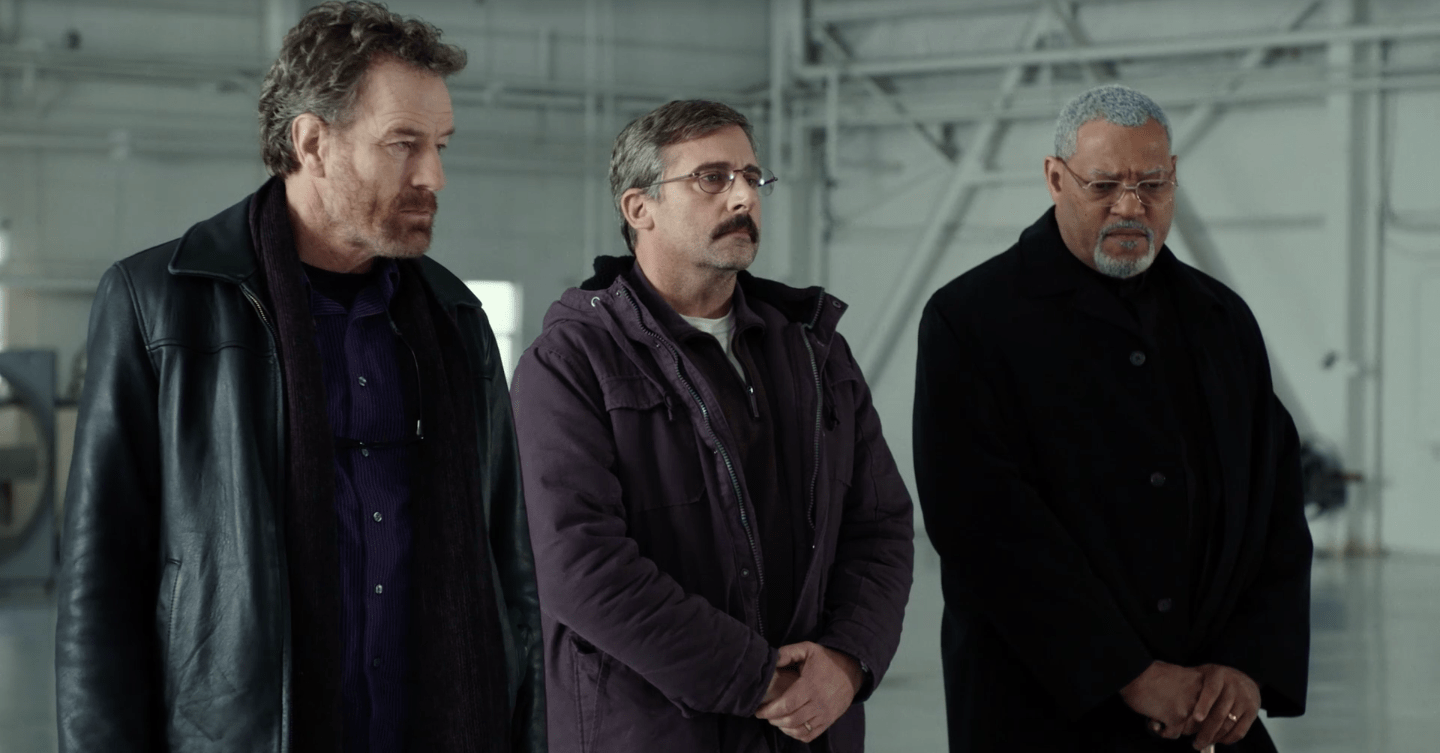

Were it not for the modification of some key details about the backstory of the characters so as to exist as a film independent of the forty-four year old The Last Detail, Last Flag Flying‘s set-up would be a nearly perfect translation of the book. Doc (Steve Carell) tracks down his old Navy buddies, the foul-mouthed Sal (Bryan Cranston) and the surprisingly pastoral Mueller (Lawrence Fishburne), in the wake of his Marine son’s death in the Iraq war. Enlisting the emotional and logistical support of his old service mates, Doc goes to retrieve his son’s body, only to have Sal and Mueller influence his weary psyche like a devil and angel on his shoulder as he must make vital funeral decisions.

What makes Linklater work for this material is that, given how much narrative set-up is required before these characters can shoot the breeze, he is forced to develop his cast into characters beyond their archetypal function in the group dynamic. Carrell handily pulls off the nebbish beta male persona, taking direction from those he looks up to even as he is ultimately the one who needs to step up and cope with his loss. Fishburne is similarly intriguing as a man who turned to God in order to escape the darkness his military past infused in him, yet still holds on to his time in the Navy with a sort of muted reverence. It’s Cranston, though, who, as usual, steals the show; as a cantankerous old drunk, Sal masks his disappointment and disgust with the world behind a wall of alcohol and humorous jabs. We’re forced to learn of these characters and their history together through this new situation they find themselves in, so by the time Linklater gives in to his impulse to let the boys just shoot the shit for a while, their character chemistry feels earned.

Where Last Flag Flying loses its luster is in translating the cynical moral complexity at the heart of Ponicsan’s novel. The central conflict involves straddling a line between allowing the families of fallen soldiers the comfort of thinking their dead fell as heroes and exposing how that universal platitude perpetuates a culture of war which results in more dead with every passing generation. These two perspectives exist in a complex disharmony in the novel that, whether due to a softening in Ponicsan’s sensibilities or through Linklater’s influence in drafting the screenplay, becomes entirely simplified for the sake of a feel-good sentiment about honoring the troops. This isn’t to say that the film’s character arcs don’t work in this context—they do—but the potential to leave difficult questions hanging is discarded in favor of a disappointingly clean conclusion.

Even so, this is the most grounded Linklater has been in a long time, and while many relate to his laid back masculine chill, I found Last Flag Flying a refreshing redirection of his talents. Though the film lacks much of the subtlety of its source material, it remains an engaging and entertaining trip with a group of charming characters, propelled by performances that do those characters justice.