Few films are as pure a character study as Michael Clayton, the story of a troubled legal “fixer” caught up in a profession that has brought him nothing but pain and strife. There is a fleshed-out world that Michael exists in, but just about everyone he knows and meets through our time spent with him is a reflection of himself in some way, a glimpse at who Michael currently is, who he might have once been, and who he could have turned out to be. Released ten years ago today, Michael Clayton stands the test of time as an engrossing legal thriller, but the man at the center of the drama is infinitely more important than the circumstances that surround him.

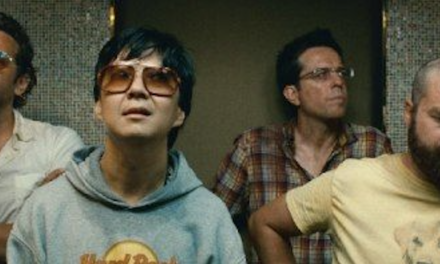

To understand Michael, though, we have to know who the players of this character piece are. Michael (George Clooney) is a divorcee, a habitual gambler whose addiction forces him to keep working in a job that alienated him from his wife and continues to strain his relationship with his pre-teen son Henry. His firm enlists him to bring under control one of the firm’s leading attorneys, Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson), who suffered a manic episode in the middle of a deposition hearing for a high stakes lawsuit against an agricultural conglomerate, U-North. On U-North’s side of the table, another fixer, Karen Crowder (Tilda Swinton), discovers that Arthur is in possession of a memo that implicates U-North in knowingly distributing a cancer-causing weed killer, so she has to take measures to remove Arthur, and consequentially Michael, from the picture.

However, the movie is called Michael Clayton, not The Carcinogenic Weed Killer Caper, so it’s clear that we’re supposed to care less about the mechanics of the plot than we are to care for Michael’s personal struggles, which Arthur and Karen give us a substantial framework to do so. Let’s start with Arthur, an attorney that suffers from manic episodes under the strain of his high-powered life. Unlike Michael, he doesn’t appear to have a family that he squandered away on professionalism, but this also means that he has no one to rely upon except for Michael the company man, who himself is relied upon by his own family more than he relies on them. They are both solitary creatures trapped by their professions, though Michael is envious of Arthur’s position and cannot understand why Arthur cannot keep himself together when he has the affluence that Michael so desires yet cannot hold on to because of his own gambling addiction. Arthur is an expression of the life Michael wants, yet paradoxically has none of his problems fixed by living that life; if anything, his issues are only exacerbated.

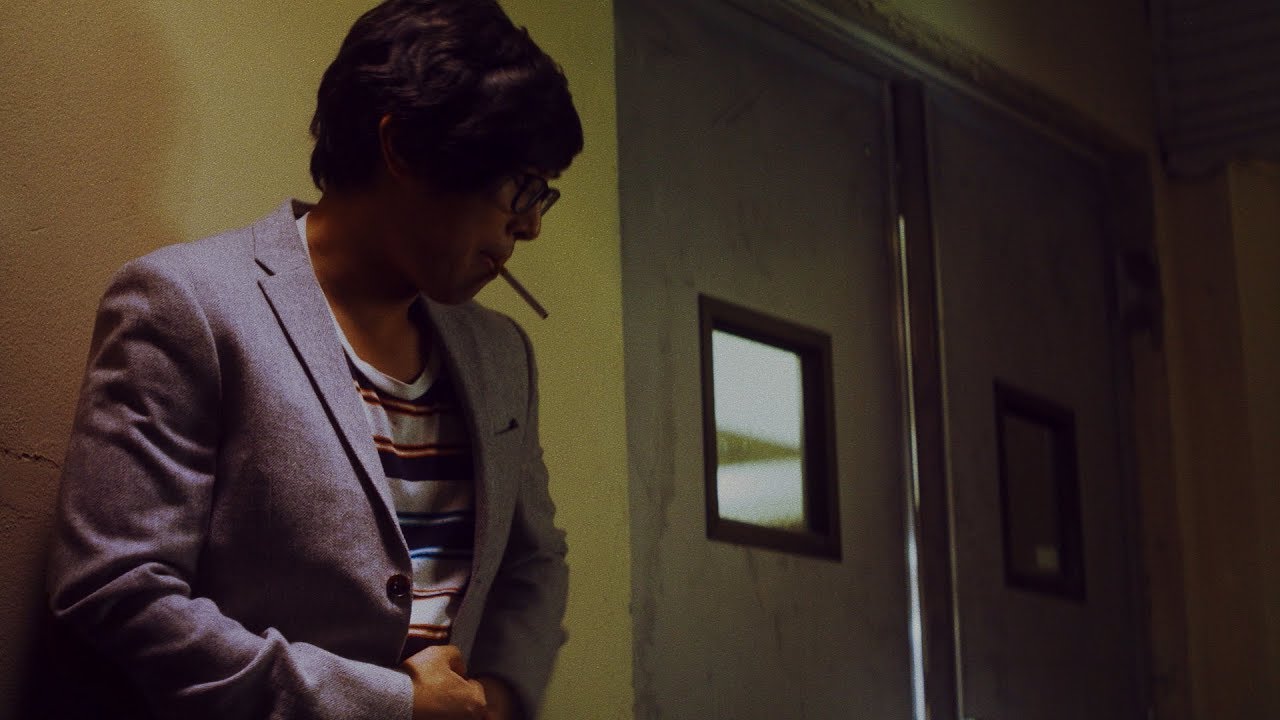

But if we’re to understand Michael’s arc through this film, we need to contrast him to Karen, the fixer who is willing to go to steps that Michael isn’t. Interestingly, Karen seems to have much more of a tortured conscience than Michael, but that doesn’t prevent her from taking the extreme step of hiring hitmen to kill Arthur and Michael for knowing too much. She is driven by greed and ambition, but she still feels pangs of guilt over having to take such an extreme and irreversible step as murder. She and Michael are committed to their jobs in nearly equal measure, but whereas Michael is in his line of work as a mechanism to compensate for his personal failings, Karen’s personal failings are what motivate her to place business interests ahead of morality. This culminates in Michael exposing Karen’s amorality as a conclusion to a character arc wherein he steps away from his own gray morality to let the legal justice system punish Karen for her transgressions.

But where does this leave Michael at the end of his story? He gets into a cab, and ending credits start to roll as he contemplates what he has just done and what it means for his future. Going back to his work as a fixer seems unlikely, as he seems to have transcended that unethical manipulation of the legal system, but what practical alternative does he have to pay off his debts and otherwise support himself? As much as he hated his work, he was good at it, and his past would likely prevent him from practicing law again in the future. His character arc was completed by accepting positive morality, but his future is uncertain and likely tragic as a consequence, which makes his choice all the more powerful. Michael Clayton often poses the question of who exactly Michael thinks he is, but when we finally get that answer, who knows what that identification of self is worth. Like Michael, we’re left to meditate upon it, and even ten years later it doesn’t feel like we have an answer.