Of all the holidays celebrated worldwide, no single day is loved by the Substream staff more than Halloween. With October’s arrival, the time has finally come to begin rolling out a slew of special features we have prepared in celebration of our favorite day.

31 Days Of Halloween is a recurring column that will run throughout the month of October. The goal of this series is to supply every Substream reader with a daily horror (or Halloween-themed) movie recommendation that is guaranteed to amplify your All Hallows’ Eve festivities. We’ll be watching every film the day it’s featured, and we hope you will follow along at home. Reader, beware, you’re in for a… spooky good time!

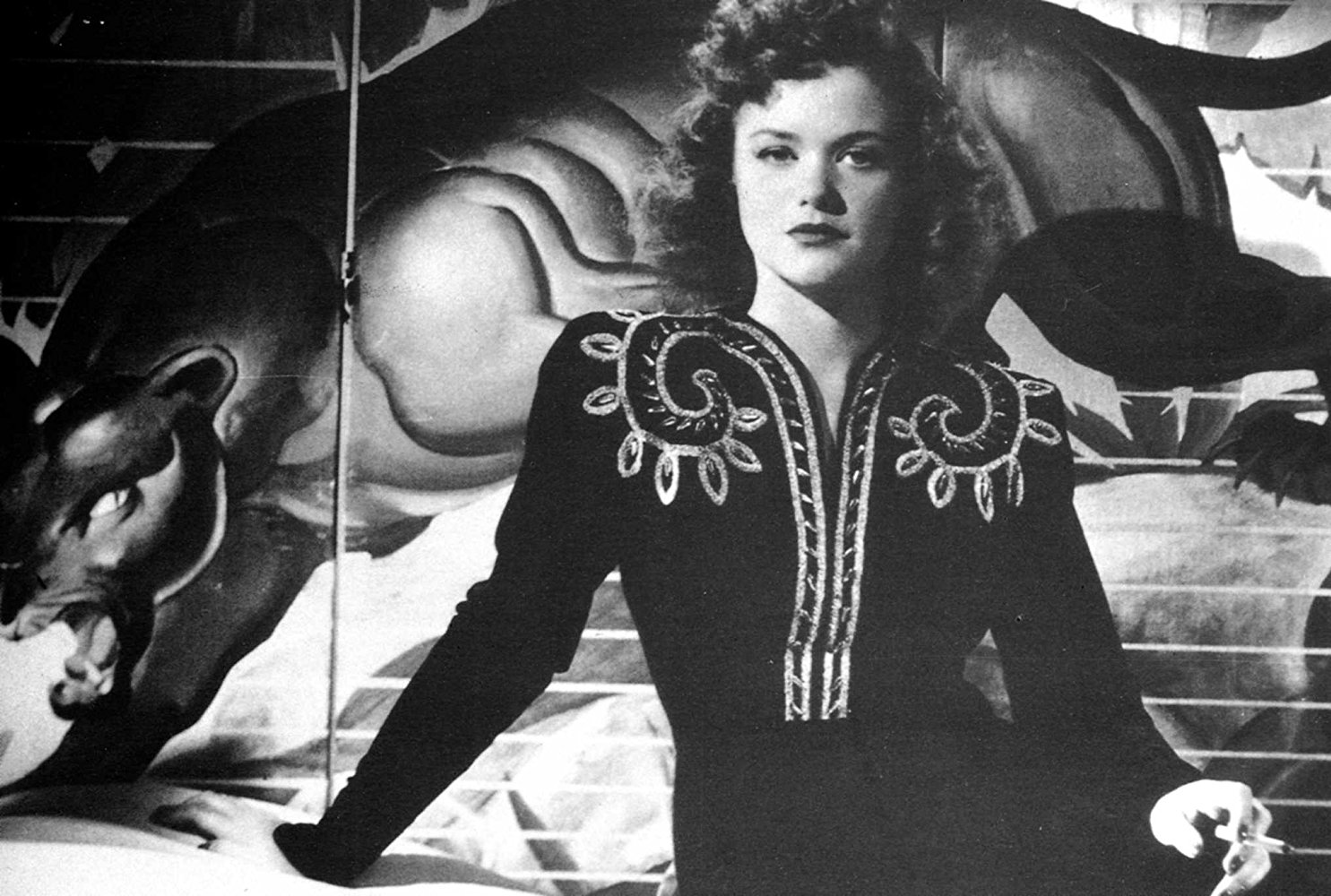

Day 19: Cat People (1942)

When people think of the origins of horror film, often their thoughts turn to films of the post-atomic age, the monster flicks that aren’t so much defined by their ability to terrify as they are explorations of the weird and fantastical through the horrified reactions of their protagonists. There are some exceptions of course; Nosferatu and Dracula come to mind, but by and large the B-movie was where horror reached its springboard as a fully realized genre. Prior to that shift, however, was the age of noir, but even then there are moments where horror found its way to the screen, even by what would now be considered unconventional and genre-bending means. 1942’s Cat People is just one such horror noir riff, and it is a fascinating marriage of psychological exploration and fright through implication.

Irena (Simone Simon) is a young woman in New York fascinated by the panther at the Central Park Zoo. While there she meets Oliver (Kent Smith), a bachelor who takes a fancy to her and wishes to court this mysterious woman. Irena is afraid for Oliver, though, as her Serbian heritage informs her of a supposed curse upon her village, wherein the women of village were prone to transform into large cats when angered by their husbands. Oliver insists they marry anyway, and upon their marriage discovers that his love for Irena wanes as he finds himself incapable of “fixing” her delusions. Meanwhile, as Oliver drifts further away from Irena and into the arms of a coworker, Irena finds herself adopting more feline characteristics, raising the question of whether she might just be a cat person.

The presentation of this mystery is never shown as explicit, though there are obvious moments where we are meant to put two and two together. Feline paw prints are shown to transform into the footprints of a woman’s heeled shoe, Irena plays with a bird in a cage as a cat would hunt its prey, and Irena follows Oliver’s new would-be love interest to an underground swimming pool, only for the other woman to be haunted by howls in the dark and come out to a bathing robe torn to shreds. These scenes are unsettling not just for what they ultimately reveal about Irena as a supernatural creature, but also because their presentation through implication hidden in shadow always offers the thought that Irena might actually simply be a jealous madwoman with a cat fixation.

However, if we take Irena’s transformations as the reality of the film—as I believe we’re supposed to—there is fertile ground to read gendered commentary of the time into her actions. She is a foreign woman, asked by male American to assimilate to his ideal of a spouse and is casually rejected when she does not abandon her Serbian traditions and beliefs. Irena is sent to a psychologist who attempts to confine her to a normalized American role of wifely subservience, to suppress her culture of origin, a culture that glamorizes the potential strength of its women. Irena becomes a monster not because of her beliefs or her origins, though that does enable the supernatural element of the metamorphosis; Irena changes because she is consistently being told to sublimate her true self, to fit into a mold of what is expected of her by a society that either expects her to assimilate or be deemed insane.

Now, it’s hard to say whether this commentary is purposeful or is a reading formed from the benefit of social growth and hindsight, but that ambiguity is part of what makes Cat People such a fascinating film to parse. It isn’t a frightening film in the modern sense of jump scares or disturbing imagery, but it is a frightening look at forced assimilation and the death of cultural and gendered individuality expressed through a monster lurking in the shadows. The fact that we’re never fully privy to Irena’s cat form is partially a product of the special effects limitations of the time, but it also places an emphasis on Irena’s humanity and alludes that maybe it isn’t her who is the real monster. Maybe the real monsters are the ones trying to hold her in a cage to ogle over like an animal in a zoo. Maybe the horrifying scenes aren’t meant to titillate us so much as they are to educate us on the power of individual identity in the face of oppressive reduction. Horror is at its finest is when it holds a mirror up to the audience to show them just how terrifying they can be. Cat People demonstrates that a monster in the shadows is frightening, but the reasons that monster is there in the first place are even more so.